Obituary

Dr. Hans Lobenhoffer deceased

Dr. rer. nat. Hans Lobenhoffer, born 15th September, 1916 in Bamberg, was the last living member of the German Nanga Parbat expedition from 1939. He was accompanied in the exploration of the Rupal face of the ninth-highest mountain in the world by Peter Aufschnaiter, Heinrich Harrer and Lutz Chicken. The expedition ended with the outbreak of the Second World War and the internment of the Germans in India. Whilst being held as prisoners of war by the British forces, Lobenhoffer taught himself advanced mathematics.

In 1945, he returned to Germany via America and, following a carpentry apprenticeship, studied timber engineering in Rosenheim. In addition to his activities as lecturer in Rosenheim, he also studied mechanical engineering in Munich. From 1958 onwards, he made a name for himself through managerial positions in the wood-based materials industry.

Following his retirement, Dr. Lobenhoffer obtained a doctorate in process modeling in the wood-based materials industry. During a WKI project on this subject in the 1990s, he supported Dieter Greubel through consultation and his own self-developed software for the statistical evaluation of process data.

Dr. Lobenhoffer passed away on the 14th of September, 2014 in Göttingen. He leaves behind his wife and three children.

Fraunhofer Institute for Wood Research

Dr Hans Philipp Lobenhoffer

15th September 1916 – 14th September 2014

By Roger Croston

PDF (Adobe Reader herunterladen)

The end of an era of Himalayan mountaineering has been marked by the death of Hans Lobenhoffer, the last of the pre-war generation of Himalayan climbers, a day short of his 98th birthday. In 1939, he was one of a four-man reconnaissance team scouting for a new route for a full-scale attempt of the world’s ninth highest peak, Nanga Parbat, 26,650 feet, which was proposed, but did not occur due to outbreak of the Second World War, for the following year. There was in 1939, however, no intention of an attempt on the summit.

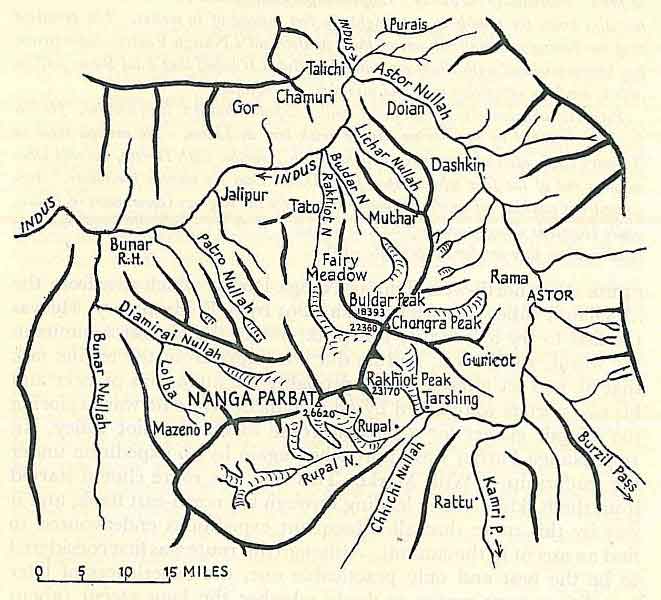

Nanga Parbat, rising a stupendous 20,000 feet above the Indus Valley, was regarded as a “German peak” – as much as Everest was regarded as “British” – but she did not treat visitors kindly, as between 1932 and 1938, eleven elite German mountaineers and eighteen porters had died in five expeditions on the exceedingly dangerous avalanche prone 9 mile Rakhiot ridge. This induced Paul Bauer of the Munich Academic Alpine Club and leader of an attempt in 1938, to seek a shorter, steeper, three-mile route from the Diamir side of the mountain. This had been attempted in 1895 by the British mountaineer A.F. Mummery with two Ghurkhas in what is still held to be an outstanding attempt, although they later disappeared exploring other areas of the peak. In 1939, Peter Aufschnaiter, an Austrian, who had been with Bauer in 1931 on Kangchenjunga, was appointed by The German Himalaya Foundation (closely linked to the Munich Academic Alpine Club), to lead the lightweight four-man expedition. He identified brilliant ice climbers – experienced in using newly developed 12-point crampons, with the innovative two front points – who could fully finance their own participation.

Initially, Max Reuss and two climbers from the first ascent of the North Face of the Eiger, Ludwig Vörg and Andreas Heckmair, were recruited. However, the latter pair were members of the Ordensburg, an organisation for nurturing future National Socialist [Nazional Socialistische Demokratic Arbeiter Partei] leaders, who would not be permitted to enter British India. Bauer entered into a difficult, lengthy and complicated power struggle with sports and mountaineering organizations and the authorities of the Third Reich as to who was suitable and the team was changed at short notice to include Heinrich Harrer (also from the Eiger ascent), Ludwig ‘Lutz’ Chicken – an Anglo-Austrian medical student and the 23 year old Hans Lobenhoffer.

Lobenhoffer was born in Würzburg Bavaria, and went to Grammar school on Bamberg where his father was a leading surgeon. He started climbing after a school excursion to mountainous Corsica and by his late teenage years, between 1932 and 1934, had made three demanding first ascents on routes on the South Wolfebnerspitze and a direct ascent of the Trettachspitze East Wall, in the Allgäuer Alps.

Little is known about many parts of his life, because he spoke little about it, even to his immediate family, but in late 1935, having moved to Rosenheim, he joined the German army’s “100th Mountain Rifle Brigade” in Bad Reichenhall and was posted to Berchtesgaden. Here, between 1937 and 1939, he climbed many great walls in the Allgauer Alps, near the Austrian border, during a boom in new technical climbing techniques innovated by keen young army mountaineers and climbing club members in the area. They raised standards to the most severe grade of “VI”. Lobenhoffer wrote, “I was curious about the pitiless smooth, overhanging, great walls for which I developed an itch. Many climbers did not revel in eight hours of such torment, but I found it very pleasing and impressive. We had to get used to using the innovative things such as rubber soles on climbing boots – just as women had newly adopted on their shoes.”

Lobenhoffer met his three Nanga Parbat companions for the first time in Munich and soon, after health checks in a low-pressure altitude chamber, they boarded the ship “The Lindenfels” in Antwerp, on 6th April, 1939, to sail for India. As the ship passed through the Suez Canal, they disembarked to sightsee, wagering a local guide at Cheops’s Pyramid who bet his camel, that they could race guideless to the top, 260 foot above, in under ten minutes; they took eight and a half, triumphantly yodelling when they arrived to the guide and his companions far below who were now busy leaving.

From Bombay, the group travelled to Rawalpindi by rail – acquiring an occasional 90 lb block of ice to cool their compartment in the train – from where they set off on 11th May with 60 porters. Crossing the Babusar Pass they reached the Indus River near Chilas on 22nd May. On the path to Halala they had a view of the exalted face of the Nanga towering 20,000 feet above. Base camp was established at 12,600 feet from where they went up the Gonolo Ridge on the opposite side of the valley. “The gigantic wall looked sheer and smooth, its rocky ribs standing out only in slight relief from the near vertical plane of the enormous face.”

On 1st June, the expedition established Base Camp, where they built a stone hut, on the Diamir glacier at 12,600 feet. Following reconnaissance from the Ganalo ridge, Lobenhoffer and Chicken climbed the historic Mummery route on 13th June and found a ten-inch piece of Mummery’s firewood in a rock basin at around 18,045 feet, which they collected as a memento. (On 6th August, 1895, Mummery had pushed up the second of three ribs of the Diamir Ice-fall and set up camp at 18,045 feet). Huge avalanches, “big enough to wipe out entire cities” crashed down all around them, sweeping up and over the sides of the mountain’s ribs. Aufschnaiter therefore ordered the Mummery route to be abandoned in favour of the adjoining rib. One other possibility remained.

Lobenhoffer now fell seriously ill, running a temperature of 104 degrees Fahrenheit and fearing for his life, he was evacuated to Base Camp, which meanwhile had been plundered by their notorious Chilas porters. Lobenhoffer recuperated and the group moved on, wanting to explore mount Rakaposhi, but found it to be forbidden to them as the mountain was too close to sensitive international borders. So in mid July, they returned to the Nanga where, climbing carefully, Harrer and Lobenhoffer established Camp 4 on “The Pulpit”, at 21,300 feet, taking 10 hours from Camp 3; their ability to use the new style 12-point crampons, with two points sticking out at front, proving invaluable. They compared the route to “the worst parts of the Eiger or the Brenva flank of Mont Blanc,” as stones whistled over their heads indiscriminately. (Nanga Parbat was eventually climbed by Hermann Buhl, a one-time climbing companion of Lobenhoffer’s, on 3rd July, 1953, who was benighted, standing on a steeply angled rock at 26,000 feet without shelter, food or water, in what is still considered the most outstanding solo ascent of any Himalayan giant).

On 26th July, the reconnaisance being successfully concluded and with Diamir Peak (18,274 feet) and Ganolo Peak (20,997 feet) having been successfully climbed, Harrer and Lobenhoffer travelled with the bulk of equipment to the Rakhiot Bridge in the Indus Valley and on to Bunji and Astor, while Aufschnaiter and Chicken went to thank the British Political Officer in Gilgit who sounded out their political views and reported them to central government.

Returning to Srinagar on 24th August, “looking like a group of mountain vagabonds with unkempt hair and beards,” having had no contact with the outside world, they were astonished to hear about impending war. So they soon set off for Karachi to return home. They sought voyage home on the ship “The Uhlenfels” which, however, had been instructed not to approach India. Unable to find other ships or aircraft, Harrer, Chicken and Lobenhoffer attempted to reach Persia “along the route of Alexander the Great” via the Principality of Las Belas, Beluchistan, whose Maharaja, they had been told no friend of the British, might be of help. This was an idea that Aufschnaiter thought doomed and he stayed in Karachi to look after the expedition equipment. They were however, being watched and word reached the [British] India Office where an official noted ‘I’m afraid they are going to have considerable difficulty in getting home unless they left India before 29th August.’

The attempt to flee ended abruptly when, after bivouacking, the three were apprehended for travelling without papers; newspapers stating that aliens leaving main roads were liable to ten years’ imprisonment. The superintendent of police received them with, ‘Well gentlemen, you lost your way while hunting, didn’t you?’ to which they replied “Yes, Sir!” Archived intelligence relates: ‘The superintendent of Police … stated there was nothing suspicious about them, except an intense desire to get away to Germany before war broke out. There was no case against them… the four came prominently to our notice on account of the rush tactics they adopted in getting to India… We are now trying to find out something about them and if they did any serious climbing.’

The four were interned as civilians under the Geneva Convention in the Central Internment Camp, Ahmadnagar, and their baggage impounded. In 1941 they were moved to Deolali, north east of Bombay which provided an escape opportunity when Lobenhoffer and Harrer jumped from the back of a moving truck in convoy when a guard was distracted. They were immediately detected because of rattling objects in Lobenhoffer’s rucksack – and recaptured at the point of bayonets.

Deolali was unbearably hot with dusty, poor accommodation, so all went on hunger strike for better conditions, which resulted in a move to a new purpose built camp at Premnagar, Dehra Dun, Mussoorie. The move there provided another escape opportunity, as archived: ‘Superintendent of Police, Delhi. On the evening of 10th October 1941 a train conveying internees from Deolali to Dehra Dun halted for two hours at Delhi. It was discovered Lobenhoffer, internee No. 1085, was missing. He was re-arrested at Puri, Orissa, 13th October. The arrangements by the Military escort for the safe custody of these internees appear to have left much to be desired.”

Lobenhoffer recalled the intense boredom in camp, which was relieved when he sent a request to an uncle in the USA to send him a book on mathematics which he seriously studied. In camp he played much football and handball and the granting of daylong parole in the hills surrounding the camp relieved the tedium. He escaped again in a lone attempt “over the wire” on 2nd June 1942, when no one else at the time was interested to flee. He was caught almost four weeks later at Londa, close to the Portuguese enclave of Goa. [Unfortunately, nothing is known about what he did during this time. When a friend relayed written questions to him in old age about his earlier life, he did not answer, but would only smile and gently shake his head].

The expedition’s 39 rolls of still photographs had been confiscated and Aufschnaiter demanded their return. They were withheld because of Lobenhoffer’s escapes, and considered as ‘maps’. However, a British official stated that ‘revenge was not to be taken and internees were entitled to possessions if not proscribed, and the films were handed to the care of the commandant. Sadly, many of the films were lost and never returned.

Lobenhoffer upon arrest, had described himself as a ‘Government Official’. Much later in Dehra Dun, in February 1941, he claimed to be an army officer and demanded correct pay, He claimed he had been detailed to accompany the expedition. However, the archives state: ‘There is nothing in our papers to show that Lobenhoffer was, as now claimed, detailed by the German High Command to accompany the Expedition.’ In fact, enquiry via the Swiss Consul confirmed that he was a lieutenant employed as an army mountaineering guide on 220 Marks a month and he had been commissioned on 1st January, 1938, in the ‘100th Mountain Rifle Brigade.’ He had received a letter from his Commandant written in July 1939 “Since your departure to the fairy [sic] country of India, all of us followed with pride your activity on Nanga Parbat… Your reports are read with great interest… I transmit in the name of the whole Regiment our heartiest wishes for a further successful continuation of your Alpine work.”

Lobenhoffer persuaded the British that he should be treated as an “Officer Prisoner of War” and so he was transferred to Halifax, Canada, where, years later Harrer reported, at the war’s end Lobenhoffer faked insanity in order to be transported home early.

Back home he lived in Bad Reichenhall and in Rosenheim, where he often skied with Harrer and, as one of the best technical climbers of his day, he made his greatest achievements in severe technical mountaineering; including in 1946, the first ascent of the southeast wall of the Kleinen Muhlsturzhorns; in 1947 the first winter ascent of the Gollrichters; in 1948 one of the first repeats of the extremely difficult ‘Haystack’ of the lower Schüsselkarturm; in 1949 the first southwest wall of the Kleinen Muhlsturzhorns. He went on to even greater achievements. In 1950 he tackled the North wall of the Westlichen Zinne (Cassin), one of the two most severe walls of the Dolomites – almost 2,000 feet of smooth, overhanging rock with no possibility of retreat, which had only been climbed nine times since 1935. Setting off with Rudi Schreiber they were astonished to find two Italians in front of them. That night, he felt “none of the supposed romance of bivouacking as often cited in mountaineering literature”, when he was hanging off four pitons with his feet dangling in the air. Reaching the top he recorded, ”it was an old dream fulfilled.”

He also thoroughly enjoyed the Mont Blanc group, even talking his friends and wife into climbing the “Classic” 15-hour Charmoz-Grepon route as an introductory tour; the most difficult part being the summit ridge, above huge abysses. In 1954 Lobenhoffer and Juergen Wellenkamp tackled the 3,300-foot Grandes Charmoz North Wall, a rock and ice route, previously ascended by only half a dozen. “Going up a very steep ice-field, we must have looked like two flies climbing up a glass.” Having dried their clothes from a thunderstorm they then set off up the granite of the east ridge of the Dent Du Crocodil and Caiman, followed by ascending the Aiguille Du Plan at 12,140 feet – a huge mountain tour in one day.

About these “Aiguilles” of Mont Blanc he wrote, “they are one moment alluring, then bleak, then ice cold, then sunny and warm, sometimes easy, then tenaciously hard won. Only those who take it upon themselves to scale such peaks, can fully master them.”

Between 1955 and 1959 he was chairman of Rosenheim branch of the German Alpine Club. From 1949 until the mid 1950s he published articles about his climbs. In these he described adventures on great rock walls involving desperate overhangs and long traverses, sometimes finding the rope too short; getting well and truly frozen in fog, mist and cold winds; going hungry and being enthralled by remarkable meteorological phenomena – such as cloud colours ranging from grey through all shades of blue to ultramarine.

He organised the first German Expedition to Nepal of 1955 to the little known area north of Annapurna, in which he had planned to participate in a group of eight mountaineers and scientist. In the event, only four climbers went because his mountaineering was to take a back seat as his professional career developed.

In Canada, Lobenhoffer had been detailed to work in the P-O-W camp’s carpentry shop. The skills he learnt became the basis for an outstanding career in wood technology when he returned to Germany. He began from nothing in 1945 and established a small workshop, repairing broken machinery here and there meanwhile studying engineering at the Technical University, Munich. He had taught himself advanced mathematics during his long incarceration. “I always annoyed the lecturers when looking at their tabulated calculations, telling them this was wrong, that was wrong, and that…” Later, he himself became a lecturer in wood technology at the Rosenheim Wood Technical College and worked in the flake and fibreboard industry where he became an international expert in decorated, varnished, surface finishes. Between 1958 and 1963 he built up a factory in Ireland producing innovative, high quality materials, much to the distress of competitors. He published technical papers in 1958 on varnishes, their drying, hardness and aging.

In 1968 he was technical director for Novopan Ltd. in Göttingen where he settled to live; later becoming manager of Glunz Ltd. Completing a doctorate “Control Mechanisms for the Evaporation of Formaldehyde from Fibre Boards”, after retirement in 1990, for which he developed complicated mathematical models which until then were little understood. This was of especial importance in furniture. He also developed “Real-Time” computerised, top quality mass production monitoring. From 1988, he wrote 19 technical papers and co-authored two books. As with all pioneers, he was initially scoffed at, but now the “Lobenhoffer Visionary Standards” have been adopted industry wide. Despite failing eyesight, at the age of 93 – so as to complete his life’s work – he was still intensively writing instruction manuals for the industry, especially following a scandal in California where imported fiber boards from China leaked formaldehyde. Boards made according to Lobenhoffer’s technique leak almost nothing and he was an advisor to several American States and the German government regarding the establishment of standards and measuring methods. He co-authored two books in 1999 and 2000.

Hans Lobenhoffer’s mountaineering life had all been but forgotten in the climbing world until an interview in 2008 with Lutz Chicken, with whom he had been on Nanga Parbat, prompted a search for him. Lobenhoffer politely repeatedly declined to be interviewed or to answer any written questions; self-effacingly stating that his mountaineering story was of little consequence, until December 2010, when he spoke about Peter Aufschnaiter, for an Austrian television documentary, who, after escaping from Dehra Dun with Harrer, had spent eight years in Tibet. In his final year Hans Lobenhoffer wrote an all too short memoir; requesting nothing be published about him whilst he still lived. In his final days, he continued to pay much attention to hearing about

He married firstly Gertraud Pflanz in 1951 (later divorced) with whom he had a son Phillip, who is a professor of sports orthopaedic surgeon and secondly, he married Uta Werner in 1963.

He is survived by his widow, son Philipp and daughters Petra and Claudia.

Links